An interesting photograph and an interesting story exploit the strengths of two very different media.

To start with, they operate at different bandwidths using different tools. The camera shows a “what” but not a background, a “how”, while the pen tells the background and the “why” but is overly verbose in capturing and describing the “what”.

Telling a story requires a reader’s own knowledge of characters in situations, their motives, and the ways they behave, in order to achieve communication. We expect that though readers bring different experiences to their side of the background fill-in, those would be similar enough for our purposes.

While the camera also relies on shared expectations and knowledge from viewers (perhaps even more so than the pen?) it doesn’t explain the end result but simply shows it, leaving us to make our own inferences about who they are and what brought them to this place and shaped them in this way.

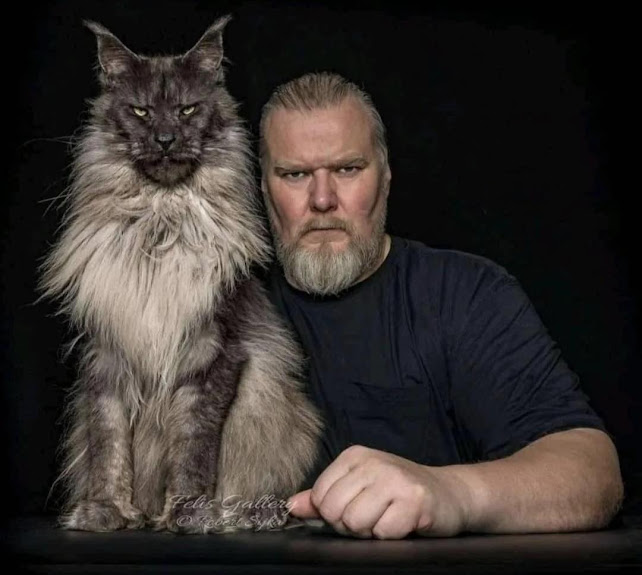

For writers, these distinctions can color our prose. Let’s say that the illustration above referenced the start of a story. There is clearly a shared history for these characters. Given an image like this in our heads, the prose story might start with:

“They’d been companions for most of their lives, long enough to get used to their differences without ever quite forgetting them, the way the hair loss of the one was never referenced by the other, since that time when…”

But then, without the actual image presented in full to the reader, the whole cat vs man, similar intense stare, complementary coloring, sheltering embrace, age & experience, and so forth would be lost. The greater bandwidth of the medium is not fully reproduceable, without using many more words that would slow the pace down and clog up an intro.

I tend to ruminate on my stories for a while before I write them, running my characters through their paces while I decide what should be happening with them, in what sequence, and why, sort of like a personal film with god-like telepathic special effects so that I understand the “why”. I have to remember to appropriately represent in the writing of the story those things which I just know from my authorial position, those perceptions which I have pulled from the private film and what that suggested/felt like to me. I can view that film, but my readers can’t, not unless I help them. I may have to use a density of scattered backstory snippits to approximate the bandwidth of my original film.

What sorts of media translations do you run across when writing (or reading or viewing)? How much of what you write is hard to translate from visual language? Or is it all fairytale castles in the air, sketched out with waved hands in the smoke of the campfire?

9 responses to “Media: Camera vs Pen”

Wow. They do say people start to look like their pets …

Describing landscape is hard to transcribe. How exactly does the land change? What is the way to describe how the stones of the wall gradually change color, because of their different ages? What’s the best way to explain the shifting shadows on the folds of the waves beyond the castle? People are comparatively easy compared to land, at least for me. Photos are far clearer for landscape than are words, unless scents and sounds are needed as well.

Rather than trying to get at it directly, I sometimes do it obliquely, via the embodied emotions of a character. “He paused to take a deep breath of the valley air that swept into view as he reached the top of the ridge and accepted the excuse to pause and admire.”

But it’s not the same as seeing it for real, of course.

The two big things I note about description in prose are that you can load your language — it matters a lot if your woman is in dressed in a rose-red or a ruby-red or a blood-red ballgown — and that you can, and in fact really ought to, use point of view to notice what the character would notice.

Part of it, it seems to me, is that it doesn’t matter what the thing you’re describing looks like to you, it matters what it looks like/feels like to the character, and thus to the reader. The description is all in service of that, not of painting a detail in a bravura exercise.

All three of those descriptions of red don’t signify tones of red to me at all, but the what they mean in the context of the story. They’re all just “red” to me. “Rose red” means the ballgown makes her look pretty and feminine, and is romantic. “Ruby red” implies wealth and nobility. “Blood red” implies dangerous, deadly.

Then again, apparently I don’t see images in my mind like most people do. And I am unable to keep more than three colors, even at the basic color level, in my mind at once.

If I have to describe a visual in detail, I have to find an image somewhere to describe while I’m writing.

Ditto.

If it’s not about the woman wearing them, it’s about the person describing it.

I’ve got an Evil Earth Empire where the guy has no religion and a massive lack of Latin in his descriptions. It hits really freaking weird.

Exactly!

Though that sort of loading can be heavy-handed. If she has spun-gold hair, pearly skin, sapphire eyes, and a ruby-red gown, the reader’s likely to grumble about the hammer effect. OTOH, if she has spun-gold hair, milk-white skin, sky-blue eyes, and a blood-red gown, it has the effect of a mixed metaphor.

Plus the POV effects. OTOH, we allow more reliability to POV characters than to real people.

I just remembered a “trick” that our English teacher showed us in translating text to film– you can either do the cut-away thing (focus on a rose, cut to the girl in teh dress) or you can add say some rose embroidery and do a close focus there, then spiral out to the whole dress, so it’s a “rose red” in the impression you get.

Same way that to show Maleficent is soooooper evil, you could give her spider-web lace and do a close up of that, with tiny jet black spider gemstones.

(You know, in case they missed the whole malicious thingie)

It can be tricky. There was a discussion about *Order of the Stick* where someone pointed out that while, yes, Elan’s father had all the external marks of being a suave silver fox who could sweep women off their feet with his charm, in reality, he had offended every female character he met in the comic. So some harmony helps.