As I was trying to find audio/video works on the Silk Road, or The South Seas trade, or… something that didn’t immediately devolve into modern overlays of ethics onto what was a deeply complex system that shaped that same modern world, I was thinking about travel and it’s effect on the human.

For long centuries, many people never traveled much at all. It was dangerous, expensive, and took an enormous amount of time. Time that, if it were not your profession, compounded the expense of travel. It was assumed, at one point not that long ago, that trade between distant points of the world was either non-existent or highly restricted. And yet… we keep finding concrete evidence, in the form of durable goods, that trade was far more extensive than those original assumptions allowed for. There was the Silk Road, which was more like a yarn-skein of routes stretching from Asia into Europe, and across India or the northern Steppes. There was a route which has no name that I am aware of, running north-south from one American continent to the other. Later, when the sailing ships rediscovered parts of the globe isolated and forgotten, there were the sea trades, which were largely already well-trodden ground that had lain fallow for whatever reason – humans have short memories and long storied traditions, which may seem like a contradiction until you stop and think about it. Mythology and legend aren’t real… are they? How much of them is based on something that happened, and where is that line?

Take, for instance, the cargo cults. Or, as was discussed yesterday over at Alma Boykin’s blog, the influences as seen on the armor of the terracotta army of China. Just how far into the North American continent did the Vikings and their kin get? There is room for endless speculation, and some of it is very ripe for story fodder.

What I wanted, though, was something to keep my brain busy during the day job, when my hands are busy but the mind isn’t. Reading time for research is limited, so I thought I’d be able to find a documentary or something on the topics, and came up with very little on the South Seas trading (which is my loose basis for the trading ship route in the Tanager series) and a lot on the Silk Road, but most of it very shallow. Sadly, the ruinous influence of Islam in the center of the routes has erased much of the art and architecture that showed the wonderful cultures that used to be there, springing up at caves and strategic points strung out over some of the most forbidding terrain on our globe. What’s left is bare rubble and guesses, and those only able to be made by rare archaeological expeditions that are allowed into parts which are nominally safe. It would be fascinating to learn more, and I’m frustrated by the dearth of material.

Which means I’ll have to make up my own stories. Only mine are set in space, with planets for the caravanserai. In that, I join the history of travel legends. Those who traveled, making up stories to elide the dust and filth and dangers they had overcome, like Marco Polo. Those who never traveled making up what might be out there, past the far horizon, over the blue hills and out into the realms of draconis.

I should see if some of the antique travelogues have been done up on Librivox. Many of them were outrageous bordering on silly, but they were a blend of fiction with non-fiction, so they might be rich fodder for a fiction writer. Aha! There are a lot of them. This should be fun!

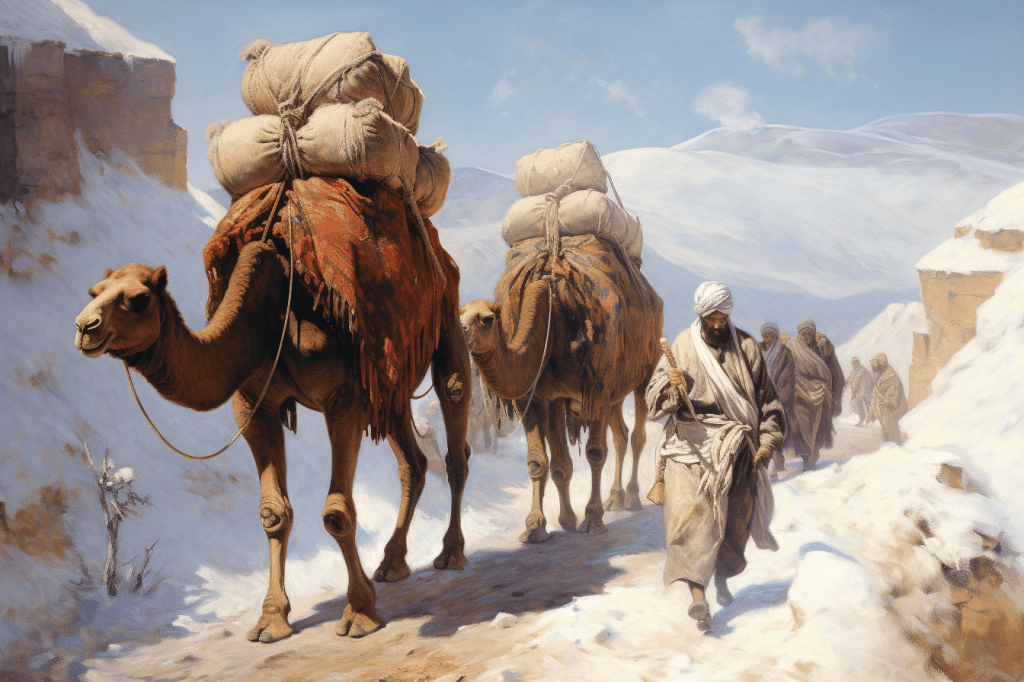

Illustrations are by Cedar Sanderson, rendered with MidJourney.

26 responses to “Legendary History”

You might look into town origins as a source. Novgorod was founded in the 900s as a northern trade hub. Stayed thatvway until Ivan the terrible burned it in 1565 so he could shift the trade to Moscow. Volgograd, then Tsaritsin, was founded in 1589 to facilitate trade up river from Iran and the Middle East and across the southern Russias.

Alma Boykin’s “Imperial Magic” book was based on that from around 1250, and she has a list of sources in the back. Excellent book, and the whole series too.

I wonder why Richard Halliburton isn’t in Project Gutenberg. I don’t remember specifics of his stories, just that they were fun to read. And you can buy at least one of his books from 1925, very easily.

1. Looks like he is barely remembered.

2. Looking at a couple of his books on the Archive, they are heavy with photographs (because travel books), and photos adds a bit of complexity to converting to ebook. Including the pics, making sure they look good and are scalable, etc. In addition, you want the best versions you can find which, with rare books, is even more of a time investment.

3. His next of kin and his publisher look to have been at least somewhat diligent about copyright renewal registrations:

https://exhibits.stanford.edu/copyrightrenewals/catalog?exhibit_id=copyrightrenewals&search_field=search&q=Richard+Halliburton

Meaning that only the two books he published prior to 1929 are in the public domain, for sure. (As he died in 1939, his stuff is actually PD in most of the world, but not here in the US.)

I wonder if it’s also that some people find him ‘problematic’ these days. He did write some really bizarre yet entertaining things. I think it was Halliburton or Seabrook who was the source for the idea of the Yazidis being murderous devil-worshipers, for one thing.

I mean, he was an explorer in the first half of the 20th century. He’s all but guaranteed to be branded a racist, on that alone.

Unfortunately, yes.

Though after reading some of the books those people wrote, I do occasionally stumble across something that by modern standards is so vicious that I can get why some people get all hot and bothered. See if you can ever find a copy of “Our Cannibal Cousins”, written about the US occupation of Haiti in the 1920’s. I’m not very sensitive, but I almost fell out of my chair a few times when I read part of it.

Oh, by modern standards, everybody then was racist, for sure. But there are degrees of these things, and someone willing to go exploring in strange cultures was, at a minimum, open to them. Possibly (probably) condescending and other unpleasant things, but also unlikely to be a KKK member.

I suspect Haiti is a special case, in all sorts of ways.

Did you come across this series? In 1980 a Japanese TV crew went with some archaeologists and traveled the entire length of the Silk Road within the borders of China. Modes of transport ranged from trucks and trains to camels. I found the later sections once they got to the far western regions fascinating.

Thanks! I had put it in the playlist, but will bump it closer to the top – I’ve been adding and deleting as I start to watch and figure out if it’s useful (mostly not).

I second the series. I watched it in college 1.0 when I took a class on the Silk Road. I don’t remember any real PCness or politics, just increasingly harsh conditions that the crew had to deal with as they went west. Oh, and the soundtrack by Kitaro, because I was a big Kitaro fan back in the 80s-90s.

I mentioned that I’ve been reading Cooper’s The Spy. One of the characters is a peddler, who as near as I can tell, spends his entire life walking between towns with a pack of whatever is compact and valuable enough to be worth buying and selling,

He pretty much eats based on the rules of hospitality brings the scuttlebutt, and buys/sells things with the households he stays at. Apparently he’s got a huge pile of money back at his house, but enjoys being on the road too much to actually stop doing it.

Thing is, the book was written in 1820. And as near as I can tell, that’s basically the way it worked. I think most rural areas either had a surplus, so one more at the table wasn’t worth tracking, or they had a deficit and would simply turn people away. And it was probably only in cities or towns that you’d have food and lodging tracked by money exchange.

I’m thinking people generally didn’t rob strangers on the road, first because you could get really hurt, and you generally couldn’t get much you could use from it. And you wouldn’t have a peddler coming by any more.

In a way it is the inverse of the future empire problem: instead of needing to figure out how having trillions of people would impact the society, instead you need to figure out how a country would function with a population less than Dallas Texas.

A peddler was a known person. The best thing after a settled person was a person with a set route, and who was useful. Tradesmen like cobblers who could not live off a rural area without moving had the same protection.

Thing is, I don’t think it’s just known persons. It seems like any person who seems reasonably not hostile may get to crash there, provided it’s not basically just a lone woman living there.

Ended up watching an interesting thing on game theory and the prisoner’s dilemma, and one of the thing that came out of it was it was almost always better to cooperate with the assumption you would see the other person again than it was to try and hose them on the last exchange.

In that context, especially without a lot of low effort food preservation, if you’ve got a surplus, it makes sense that it’s not a lot of skin off one’s back to host a passer-through for a few days. Plus you’ll get new news to hear about.

If it made sense not to rob and kill passers-through, then why can you find so many stories dating back to the tale of Theseus about murderous innkeepers killing the guests?

Because people aren’t rational creatures, they are rationalizing ones. Just because it makes sense in general to abide by and to provide hospitality – and we have myths from ancient Greece and earlier pointing out that humans should do precisely that, from both sides…

…doesn’t mean that a comparatively wealthy person whom “no one will miss” wasn’t a tempting target, and there were people aplenty who’d fall to temptation. And that the strangers themselves weren’t occasionally there for a more sinister purpose than passing through.

The Glencoe Massacre can still be felt by those sensitive enough to the land, coming up 400 years later, and it’s not wise to be a Campbell in the area. Why? Because they stayed with their hosts over 3 days before killing them, breaking all the ancient traditions of hospitality. That was the unforgiveable sin, that put them beyond the pale.

In the 1870’s? Ah, it was often safe to be a traveller… unless your hosts were the Bloody Benders, eh? The reason they went so undetected for so long was that they picked and chose upon whom they preyed. It wasn’t every guest under their roof, but lone men carrying large sums of cash, with no nearby relatives.

There’s a reason why hospitality and hostile derive from the same root. Also “host” in its meaning of “person who receives guests” and that of “army.”

Also, America was just about all frontier. With an abundance of land and a lack of labor, its standard of living was higher than anywhere in Europe.

The Silk Road also had an incredible impact on society. Back when I was in seminary I noticed the incredibly strong influence Buddhism had on Christianity. I know I annoyed a number of devout Christians by pointing out the influence of practice and discipline that Buddhism had on Christianity. I also offended a few devout Buddhists by pointing out some of the similarities between Catholic practices and Buddhist practices, such as meditating to a mandala vs. the Stations of the Cross. There is also the practice of celibacy and poverty in both Theravedan Buddhism and Catholic clergy.

It’s not a video, but the book By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia by Barry Cunliffe traces trade and the movement of ideas and peoples back and forth, starting in the Neolithic. It’s very well written, and has lots and lots of maps.

I think I have a copy of that, and if not, I’ll borrow Jim’s. Thank you, it’s one I have been wanting to read anyway.

Highly recommend! Was going to recommend, but Alma beat me to it.

And I do have it in ebook, so it’s now my bedtime read for the foreseeable future.

Once upon a time I was an Anthropology major (before The Fall, as it were) and learned there was a continental trade in pipe stone all over North America. Soapstone pipes were common among Indian tribes from the north of BC and Ontario to Florida and the Southwest desert. The most highly prized was the red pipestone from Minnesota.

There’s a town named Pipestone and a national monument. About the only things of interest in the whole place, really.

When I lived there I made pilgrimage down to the Source of the famed red pipestone, which turned out to be a very un-exciting shallow hole in the middle of a park. There’s still red stone in it, and the local Indian tribe still quarries it out occasionally. Not much call for it anymore, apparently.

But the history of trade routes and primitive trade is quite well studied in North America, thanks to that red soapstone. All the good work on it done pre-1980s of course, the Woke have pretty much destroyed archaeology since.

That, and the lovely purple chertz out of the Alibates flint quarries in Amarillo, TX, that is unique enough we can trace trade routes out to North Carolina.

The flint quarry is much more exciting with a ranger as a guide, because they can turn the shallow depression and rocks underfoot into here is where they mined, here are the rocks they sat at to knap, look around… ah, there’s one they broke, dropped in the rubble, and here’s a couple blanks on the left side that they never got to…

So you can actually crouch there and replicate exactly what the dudes did. Right down to going approximately one irritated right-handed stone’s throw away, and finding half of several broken spearheads or arrowheads. (The other half is in the rubble right at the base of the knapper’s rock. Humans don’t change much in 10,000 years, eh?)

I remember reading the same type of thing about a Clovis quarry site, of the famed “Clovis Point” spear.

https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/2021/02/08/whats-the-point-all-about-clovis-points/

The first discovery was Clovis New Mexico, but they are found all over the Southwest.

The discussion was that the Clovis point has a distinctive flute down the middle, from the base to 1/3 to 1/2 way up. That is where the wooden shaft was laid in to hold the point. At the quarry were many, -many- failed points where the flute had hinged, or it broke, or it went too far, etc. It was that last pair of flutes that were the hardest part, and they had to be done at the end, after everything else. One could see the craftsmen getting one all the way done… and then it would crap out on the last flake. So frustrating.

And yes, according to hard, measurable, repeatable archaeological evidence just like this, Humans DO NOT change much in 10,000 years. At all. Which stands in stark opposition to the fashionable notions about the Perfectibility of Man, for which there seems to be damn little evidence, but they keep going anyway.

😡

Here endeth my cranky observation for the day.