Anent the recent article on foreshadowing, I wanted to discuss something that isn’t foreshadowing, just for clarity.

In any (non-experimental) story, you want to make sure that you play fair with the reader, that you don’t show your hero with unsubstantiated knowledge of events, or violate the laws of physics (unless that’s deliberate, of course). You don’t want to trigger the flinging-book-at-wall reflex from your readers — ereader devices can be expensive.

Now, you do want to provide all the clues, especially in plot-detailed genres like mystery or crime. If you’re a certain sort of tease, you make a game out of putting important information out there for the reader without making it obvious, so that the reader, looking back, can muse, “how did I miss that?”

However, when speaking of foreshadowing, you are providing a clue to the reader, and to be fair it has to be a clue he can perceive. Only if he perceives it can he feel the suspense of “wait a minute, I wonder if that little detail is important?”

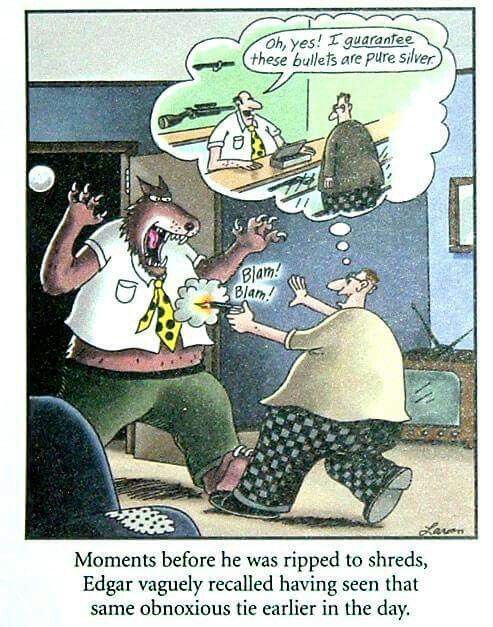

But look at this comic panel (sorry, couldn’t find a higher resolution version). As in a crime novel, the POV character can put the pieces together to identify the assailant. But neither he nor the reader could possible have anticipated that from the salesman’s guarantee. So, the salesman’s guarantee holds the logic of the plot together, but that’s all — it’s not foreshadowing. It generates surprise, for both the POV character and the reader, but no suspense.

As far as I’m concerned, that’s a wasted opportunity. I come down on the “share the suspense with the reader” side of the foreshadowing equation, not the “see how clever I am, you never suspected this could be the connection” side.

The good news is, you can always go back and slip in a foreshadowed clue to create the suspense. In this instance, I might have a scene where the POV character first tries to identify any gunsellers who deal in silver bullets, wondering if they might be acquainted with the werewolf he seeks, and finds that most of them scoff at selling silver bullets, so that the guarantee would be anomalous, and thus a detail suitable to use as foreshadowing.

How do you make your necessary plot-thread surprises into the sort of suspense that can carry the reader along? He’s yours, for as long as you can keep him… you want to make sure he enjoys the ride.

8 responses to “Don’t just cover your (plot) tracks”

Sometimes my brain foreshadows on me. My favorite case, I had an orphan girl rescued by the MC in the first book, and she turns out to be his cousin. When that happened I decided to go back to add some foreshadowing, only to find out that 1) a main character thinking her hair coloring hinted at noble blood, and 2) her hair coloring was the same as her still-living aunt’s. Just to make it more obvious I made a minor character point out that she looked a lot like her dead father did at that age.

I swear, none of this was thought out in the slightest. In fact, when I wrote her introductory scene, I thought the boy she was saved with would be the more important of the two.

That happens a lot to me. I think of it as “recycling”. I’ll introduce a minor character, for some minor purpose, and then later on it will strike me that this is just the right person to make something else happen, and I have to come up with a background to insert that grounds the history/relationship.

This is actually a good thing, since it reduces the number of extraneous characters you need when you can combine multiple actions/relationships in fewer people.

its not quite that. When I wrote Tabata in, I subconsciously added in the clues that she would be important later. It wasn’t until she let me know that she was IMPORTANT!!!! that I went back to add the clues to find they were mostly already there.

Characters — and things! — have let me know at the time that they are IMPORTANT.

That does not mean they are clear about what they signify. Or even give any details.

This is why it is important to take notes on every bit character, even more so than the major ones. You aren’t going to forget that your hero has white hair, but was the spiteful gossip of four chapters ago a red-head or a brunette?

One master writer had a story where there were clues about where a certain character had come from.

The mastery lay in that as soon as you figured out who she was, you realized that another character was looking for her, to murder her, so the mystery of who she was was replaced by the tension of wondering when this other character would twig.

Agatha Christie did this really well. I’m thinking in particular of “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd” where she hid clues inside other statements so you, dear reader, skipped over them.

Or in timing, when you don’t realize that there’s 10 minutes unaccounted for.

The fun part is that you put in the clues and some readers will complain of telegraphing, and others of a deus ex machina.

Children’s books need more clues than adult ones, because they are less skilled in decyphering them.

And then there’s where the bright and original ideas get used over and over and so everyone knows what they mean. There’s a Sherlock Holmes story where I deduced the suspect by the obvious Least Obvious Suspect aspect.