[ — Karen Myers — ]

When you tell a story about a character, you often want to provide some initial shorthand clues about him, about what he’s like. In Indo-European oral-formulaic poetry, this takes the form of an epithet, a customary adjective that can be applied almost like a label or tag, sometimes indifferently to what the character is doing. Fair-haired Achilles is still fair-haired, even when drenched in blood, and wily Odysseus is still wily even if he screws up.

A bit later, the characteristic phrase can be both formulaic and meaningful, as when Glenlogie (in the ballad) “turned around lightly, as the Gordons do all“, or it can be applied for humorous effect, for the racehorse Creeping Jane: “then she lifted up her little lily-white foot“.

In popular fiction, we use character tics — the wrinkled nose, the fastidious handwashing, the pipe smoking, the twitching hand, etc., to intrigue us or remind us of the character’s more noticeable traits, or the background that has marked him. When carried to extremes, this becomes parody.

Taken one degree further, we give the characters props – the battered hat, the broken watch, the black mask. They stand as emblems, after a fashion.

All of these things are static — shorthand labels, sometimes quite arbitrary, and sometimes (not nearly often enough) related to an actual plot purpose or character insight.

I find all of these uses (even the comic ones) to be perfunctory for most of my needs. What I want is something more urgent, more vivid – something that provides real insight into a character and his past, to give me a handle on what he might do next.

And I want the reader to do most of the work — he’ll be more invested in it that way.

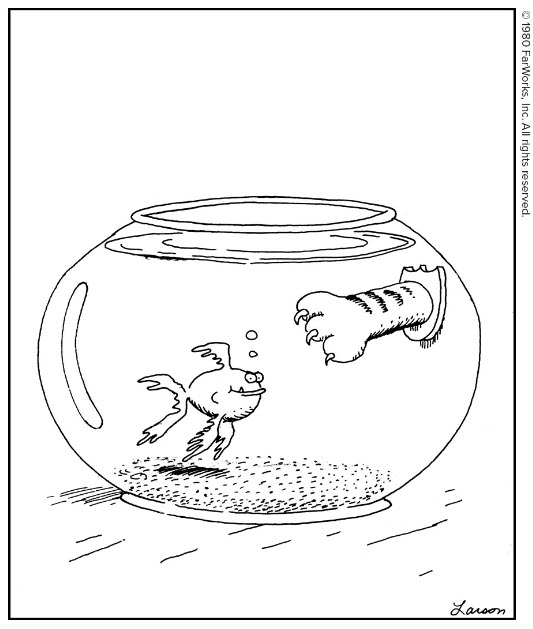

Pretend the image above is the opening scene in a story.

Premise: we have a hero with an attitude. He has a highly improbable trophy of a mortal enemy.

It’s a story prompt. Didn’t your brain skitter off into a dozen scenarios for how that might have happened? Raise a hundred questions? I know mine did — I could feel the fizz of a cluster of bottle rockets launching off in various directions.

Boy howdy, don’t you want to learn how that protagonist got here, and what he might do next?

You sure don’t need any 20-page opening, right? You could present it in a paragraph, an equivalent of the single panel comic.

Think of all the gags you could develop from that background, when he interacts with his friends and enemies. Think of all the clues it offers to how he might behave in a pinch.

If he were interviewing you for a job, wouldn’t your eye keep straying to that trophy, and wondering?

That opening paragraph is like a catalyst — it generates much more work on the part of the reader (of his own free-ish will) than it costs you. And, like a good salmon fly, it should spark so much excitement on the part of the target that he forgets there’s a hook involved.

It’s that hook that makes the difference. That trophy isn’t a prop; it’s vivid evidence of character. No one cares why Achilles is described as fair-haired, but they sure want to know what that character has to do with that trophy, and what it might mean for his future (and the voyage we’re taking with him).

How do you let your characters introduce themselves and acquire a handle? How do you make that shorthand part of the story as well as part of the character?

One response to “Give your characters a vivid handle”

Hmmm. Interesting question. I don’t consciously think of “tags” for characters. More often my mind goes to how do they move, physical appearance, things like that. Or the surrounding culture – like the goths in the Familiars series, where music and dress is a BIG part of the subculture, and the characters notice that, even in people from outside “the group.”

Hmmmm.