[— Karen Myers —]

So, you’re sitting in the front row of your rundown community theatre, alone in the audience, facing a crowd of hopeful actors milling about up on the bare stage. Their resumés looked promising, but what do you really know about them? Can they actually play the parts you have in mind?

And then there’s the (well-founded) suspicion that you don’t really know exactly what you’re looking for from them, since your process is one of discovery. Maybe that engaging rogue you had in mind for the hero really has a gaping rotten core, once you really get to know him, and you (and your reader) won’t want him to succeed after all. Maybe that tough hardened girl will grow up into a closed-off woman incapable of sympathizing with others, and no one will care that she has a pet dragon.

You’re not really going to know until you set them into action with a story and each other — especially if they’re going to be around for a long time, as in a series.

So, how do you interview the candidates? How much do you really want to know ahead of time, and what should you tell your readers? How do you find out more?

The way it works for me… I’m not the most eager and happy person in a social situation meeting a whole crowd of strangers. (That’s why god made portable books. 🙂 ) I can emulate one adequately, for a one-off situation, but for a group I will see on many occasions, I have to “live” with them for quite a while. Just matching names to faces takes serious effort, and then I have to get closer to some number of them and tune in to their tales of gossip about the others before I really get a starter handle on the situation. And that passive approach takes time.

For example, I joined a barbershop chorus almost a year ago (men’s — I’m a tenor) and while I have a list of names, I still haven’t matched all 20-ish of them to faces. Happily, I also started a quartet with three of them, and that gives me a core of history and gossip which is starting to fill the gaps. But a year is a long time for a group that meets weekly. Maybe your readers are on the lookout for the clues you drop about your characters (especially in certain genres), having ravenously digested them as they flitted by, or maybe they’re still struggling with the names.

And maybe you are confused a bit, too. Well, you built this world — you have to deal with it.

The easiest method is the stage process — run your semi-archetypes through the paces you have in mind and see how it works out. Problem is, you may find out you’ve gone quite a way into your story before something not quite right about them nags at you.

Alternatively, you can set up detailed character backgrounds to make them more subject to your stage directions. Problem with that one is the propensity for a bright idea to strike you in the middle of writing, along the lines of “what if he just happened to be fluent with Venusian because his adoptive parents…”

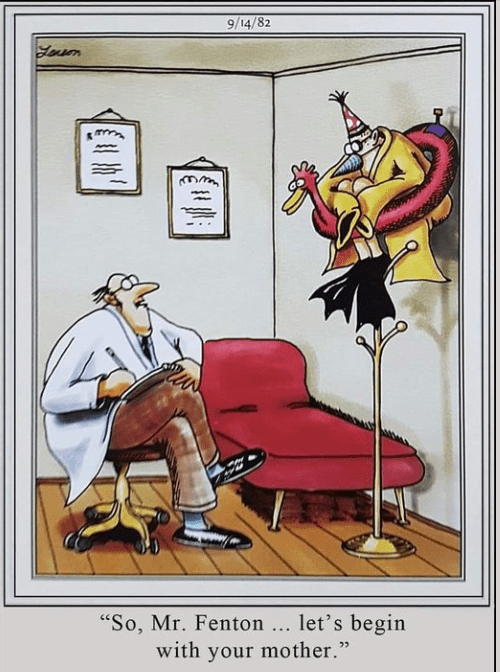

I don’t have an easy answer to suggest – I think that each of us is likely to take a different approach to the problem. The illustration above shows one: “I seem to have an odd character here and I don’t quite understand how he got that way, or what his problems are. Let me sit him down (or up in a coat rack) and conduct an interview.”

If you go that route, don’t neglect the comedy of unexpected incongruity. That smiling duck alone is worth letting this guy pass the audition and finding some role for him, if it’s not already built in. (Why the duck? Where did the duck come from? And why the perch in a tree for a swimming bird/chimera?)

What works for you? How do you interview your characters, and how much do you share with your readers?

13 responses to “Interviewing your characters”

One trick I’ve read that is used by screenwriters a lot has been quite helpful to me. Pick two characters that don’t have much to do with each other in the course of the work. They don’t have to be important characters. (Like a bartender that’s in one scene plus the hero’s sidekick.) Then give them a scene/conversation. It almost always gives me someting new to work on, and the background character usually gains from it as well.

As an introvert dealing with a bunch of less than candid characters, I tend to go for the reverse-Sherlock Holmes. Holmes infers broader, more important characteristics from slight details; I usually have the broader characteristics (appearance, day job, superhuman abilities if any, a few known activities that drive the plot) in front of me and have to infer the incidental details, the quiet scruples, who or what is putting pressure on them in certain directions. Kind of character paleontology, if you like.

When they completely stump me, I sometimes write out long-hand what the problem is, and start brainstorming possible explanations.

Same here.

And then I have them looking at me when I start crowing about figuring it out, like they’re not sure if I’m stupid or just crazy because of course….

Lol, yep.

“How do you interview your characters, and how much do you share with your readers?”

Some characters I decide to use in the story, those ones I try to know quite a bit about them. Alice Haddison, for example. I know her backstory, how she got to be the way she is, her special abilities, her special problems, what kind of truck she drives and why, favorite ice cream, preferred wardrobe, who her mom is, all that stuff.

Releasing later this week is a short-story starring Alice. She has a walk-on in Unfair Advantage, but she’s a major character in Angels Inc. The short-story is what I came up with when Sarah suggested in-between releases to bolster the main line of the series. “Alice Haddison’s Busy Day.”

Other characters, I have -no- idea who they are. A fine example are the stars of the novella I released a couple of days ago, “The Crossroads and the Oni.” The young samurai is some random guy I found lying half-dead next to a crappy tea house in feudal Japan. His character and behavior, backstory etc. I discovered right along with the readers.

The oni is another major character in Angels Inc. She’s not really human, as one might surmise with her first appearance in feudal Japan, her second in 2023. When she first turned up I had no idea who or what she might be.

Sometimes characters start out as NPCs and then pretty much demand to be included in the story. Henrietta McCaskill and Gruesome Mary started out as a cranky security guard and a lippy combat scorpion. Charlotte and Beatrice began life as disposable, insentient robots, then proclaimed they weren’t having it and ended up being main characters.

So yeah, pretty much making it up as I go. ~:D Toboggan ride, not planned descent.

One thought about “interviewing your characters” is what happens when the character is a liar?

I’d think this would more involve the “villains” of the story but may involve some of your other characters.

Many people lie to themselves so your characters may lie to you (the author).

So far, none of the characters who “pop into my head” are villains so I don’t deal with them lying to me.

Although, I have a character who is “high level thief” and he doesn’t lie about what he is (at least not to himself). IE: He may not tell the average citizen that he’s a thief but he knows what he is.

Of course, in this story universe, the defenders of “Law and Order” see him as a criminal not a villain because he doesn’t cause Big Messes (in terms of lives lost and property damage) that they have to deal with. 😉

How well do they know *themselves*?

Good point.

“Oh, me, I’m worthless, barely functional as a technician, socially stunted, don’t know why anyone puts up with me-”

In reality, polyglot who reads when *nobody* else does, brilliant engineer and has boundaries in a society that likes violating them.

Also a problem with my characters.

I’m working with a character who is suffering from some brain damage and will change once he’s accidentally caught in a magical cure. Not much, but recognizable when you look for it. . . .

He won’t notice.

My characters don’t like to talk about themselves. To me as well to other characters.

They refuse to reveal except in action.

One trick I’ve found is to stick colorless bit characters with some distinguishing trait. Use the Olympians if you want an array: this one is a bit like Hermes (mischievous), that one like Ares (bad tempered) — except the next thing they stop being colorless.