Brody, Jessica. Save the Cat! Writes a Novel: The Last Book On Novel Writing You’ll Ever Need (Ten Speed Press, 2018) Kindle E-book.

Short version: A useful and readable way to learn more about story beats, pacing, and other stuff if you need ideas, or a refresher.

Longer version: This had come up a few times on my “you might look at” list, and it happened to go on a brief sale, so I got it. I have not used any of the Save the Cat! materials, so this was my introduction to the idea. It stems from writing screen plays, which shapes how Brody approaches novel writing. If you are pretty experienced, and have a system that works for you, this might not be all that helpful. If you are new, and especially if you have trouble figuring out how to pace the action beats in your stories, or want to try a different way of outlining events in your work, this could be very helpful. The list of “genres,*” ie story archetypes, is also useful for some things.

So, it begins with plot structure, and what needs to go where. This is the first place where I sort of blinked, but keep in mind, this book is aimed at people who model their writing off of best sellers. Those of us who write in a different style might not gain as much as a newer writer, or someone who is writing more to trad-pub markets. I did find the reminder that the protagonist has to have a flaw that causes some of the story problems to be useful (I’d accidentally created a too-good protagonist. I’m changing that). The meat of the book is a timeline of action beats and scenes. It is a three-act drama, but the acts are not of equal length. If you are used to Dwight Swain’s W pattern, and try-fail sequences, you might have some difficulty matching that to this, but it can be done.

If you are a new writer and really struggle with, “OK what needs to happen now because it’s wandering off into a muddle,” Save the Cat! provides an excellent framework for finding a solution. I’m going to adapt some of it to the WIP, because my book is trying to meander off into a draggy mess. The “percentage of story” flow chart might also be useful for sorting out sequencing and problems with pacing broadly speaking (do you really need an entire extended scene about something with little bearing to the plot? Or as one beta reader phrased it, “does this carry weight?”) It also has reminders about secondary characters and their roles.

The percentage-of-story idea took me a bit to sort out. I don’t think that way, and my stories don’t always flow in the pattern Brody describes. However, the big arching point of “the opening act does this, then the middle needs A, B, and C, leading to a somewhat shorter closing act” works very well. I’m going to be applying part of that to the WIP, to see how it helps story flow. I need to differentiate the protagonist from her mother, and this will force me to approach the story in a different way than my usual. That should help me break out of a comfort zone/rut.

The third major section of the book has examples and patterns for several kinds of story, like the “Dude with a Problem,” “Monster in the House,” “Buddy Love” (not romance per se, but about relationships), “Whydunnit?” and others. Some of the examples that Brody lauds I found to be dull to borderline repulsive, BUT the pattern is the important part. And these are books that were NYT best-sellers and in some cases, picked-up by Hollywood. If you’re not sure what the core problem of the book is, these “genres” can help you sort that out, and then work from there to clarify things in the story (protagonist, event sequences, so on).

The last bit of the book also had a nice guide for writing cover copy and blurbs.

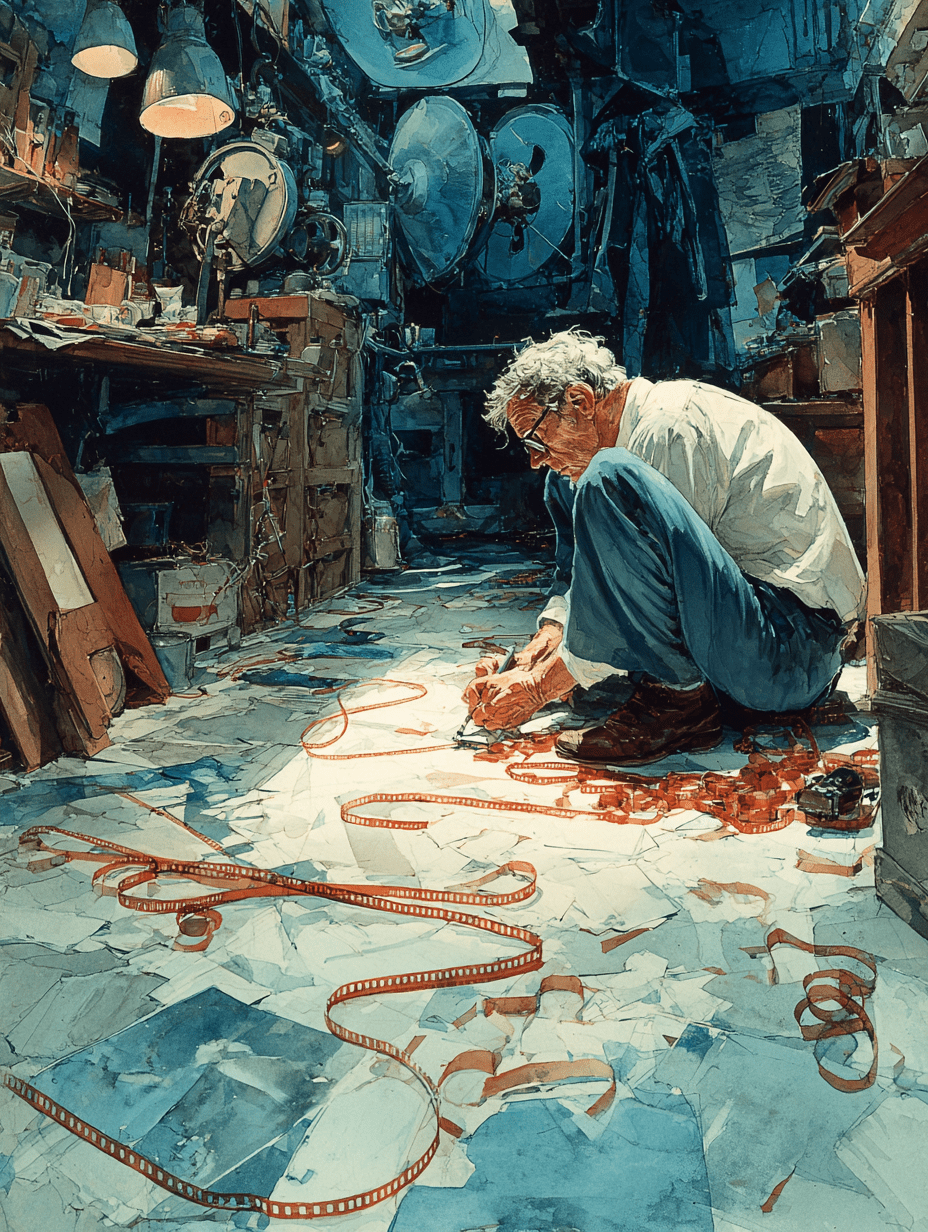

Some of the book doesn’t work for my style. Some will be very, very useful in fixing some things, and trying new ideas and approaches. If your audience inclines towards more literary fiction styles, chick-lit, and those popular genres, this is probably a fantastic book. If you are visual, and need to see how a story needs to work, or to sort things out on a story board or cork-board, this is a fantastic resource. After all, it is based on translating story ideas into a visual medium, namely screen-play into film.

In my opinion, Dwight Swain’s Techniques for Selling Writers is better overall. But if you want a relatively short, concise, visual-oriented guide to character needs, plot sequences and general pacing, and examples of story kinds, this is a great resource. You can also buy workbooks and beat-sheets that go with the Save the Cat! foundation, which might be useful if you are mentoring a complete beginner.

FTC Disclaimer: I purchased this book for my own use, and received no remuneration from the author or publisher for this review.

*Brody’s use of “genre” for “story pattern type” threw me off a little, but she applies it well, and it’s as good of a term as any for what she’s trying to describe.

12 responses to “Book Review: Save the Cat! Writes a Novel”

I have never known a writer who would say that such lists of plot types were useful.

Some find lists of character types to be useful — one to orchestrate her characters so they didn’t all turn out the same, another on the grounds that if she could identify which type the character was, the character was not deep enough. But not plots.

Don’t forget that if you write in series, all of this advice needs adjustment. Each book needs a conventional plot arc of some kind, yes, but the longer requirements and arcs of a series also need foundation and development.

This especially matters for characters, since a series will certainly have more of them. Keeping them corralled from running around and confusing the reader is essential.

Also, character flaws in a “this is just one chapter of his life” (series) sense are different from character flaws in a “has to learn how to identify villain to solve this book’s problem, and now he’s done” (single book).

The slow burn of long-term character growth in a series is not something Hollywood does well, most of the time. The Marvel Universe makes an attempt at it, but there aren’t many other examples where earlier entries are essential to understanding the current movie in a franchise.

There’s a two page guide to plot arc for sequels in a three book series. It makes some sense, but I don’t plan that far in advance.

I must admit my first thought was using “save the cat” as a signal to the reader or the viewer.

If you watch Gone Girl, notice that within the first five minutes (IIRC), Ben Affleck’s character goes home to save his cat when the neighbor calls! He’s not a decent husband and everything sets him up as the villain. But that opening scene with the cat (an orange tabby) tells you who to root for.

That’s exactly where the name comes from. If you have a protagonist who starts off unlikable, you have to do something early on to show that he/she/whatever’s not really all that bad. Rescuing a critter is a good start.

IIRC, the scriptwriter (who may have been Gillian Flynn) deliberately wrote that scene to send a clue to the audience that things were not as they appeared!

The original screenwriting book “Save the Cat” by Blake Snyder is from 2005. “Gone Girl” the book is from 2012 and the film’s from 2014.

But Hitler loved his doggies. It doesn’t really work as a test.

It doesn’t work IRL, but it does work in fiction.

It sure does! I think of it as shorthand to condense pages and pages of words.

I’m pretty sure that sometimes the real villain saves the cat. In that case, saving the cat is for giving the villain a bit of likability.

Also, I did find Brody’s list of plot types useful. I am writing a book with a murder, and an amateur who figures out who did it, and that idea has been present from the beginning in my head. But when I read Save the Cat, I saw that I was writing an institutional story and the murder is simply one move in the various machinations around the institution. That was incredibly useful. (And by useful I mean that I immediately pictured six or seven new scenes to carry this idea forward.) Unfortunately, all the lengthy examples in StC involve destroying the institution or walking away vs. joining it, and my book is about the protagonist joining the institution.

My o my. A first for me!