An appreciation of Cold Comfort Farm, by Stella Gibbons. Quotes below are from the excellent introduction in this edition by Lynne Truss.

It’s one of those books that, when you first read it, you need to not be inside the library or sitting up next to your sleeping spouse since you’ll keep laughing out loud. If you haven’t read it yet, you’re in for a treat. And if you have, this may give you a deeper appreciation of how it works. Fittingly, Virginia Woolf disapproved of its massive success as a popular work.

(Add your own first encounters and reactions in the comments.)

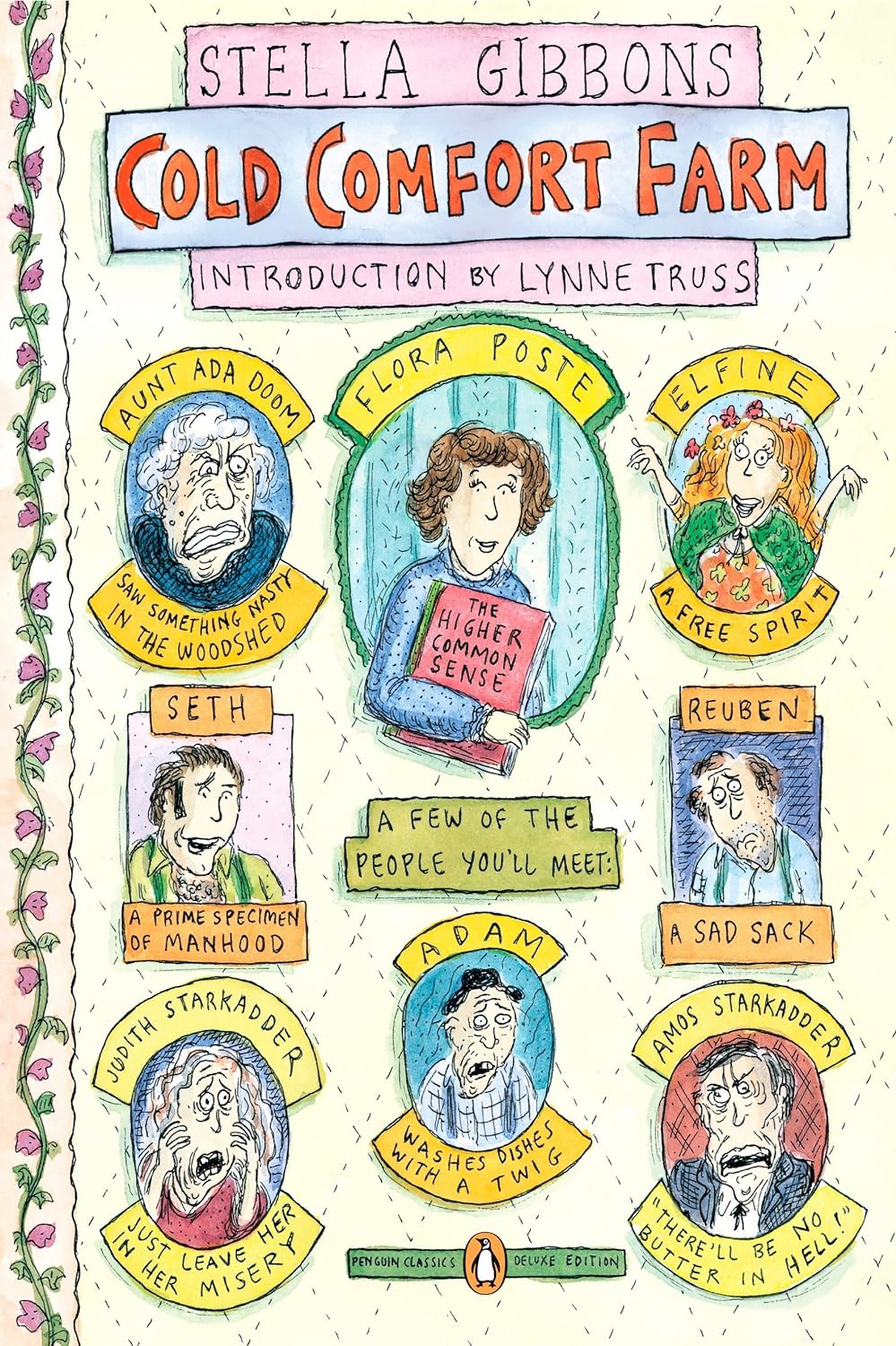

Blurb: “When sensible, sophisticated Flora Poste is orphaned at nineteen, she decides her only choice is to descend upon relatives in deepest Sussex. At the aptly named Cold Comfort Farm, she meets the doomed Starkadders: cousin Judith, heaving with remorse for unspoken wickedness; Amos, preaching fire and damnation; their sons, lustful Seth and despairing Reuben; child of nature Elfine; and crazed old Aunt Ada Doom, who has kept to her bedroom for the last twenty years. But Flora loves nothing better than to organize other people. Armed with common sense and a strong will, she resolves to take each of the family in hand.”

For a world tired of D. H. Lawrence being fashionably taken seriously as a guide for living, Stella Gibbons’ parody wherein a Bright Young Thing rusticates, and rescues everyone she meets was a popular delight.

Parody (like P. G Wodehouse) may be one of the hardest genres to pull off, but you’d never know this was her first book, written when she was in her late twenties. Published in 1932.

“Flora finds at Cold Comfort Farm a group of people who have been reduced to novelistic clichés – rather like the curvy cartoon-figure Jessica Rabbit in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), who famously drawled her existential plight, ‘I’m not bad. I’m just drawn that way.’ Flora helps each character out of his or her difficulties and they quickly find happiness. She is a character in a novel who reads the other characters as characters and rewrites them as people. It’s the ultimate narrative miracle. No wonder other writers revere Cold Comfort Farm.”

“The huge delight of Stella Gibbons’s novel is the way Flora approaches an eternal and universal difference of temperament: as a brisk, cheerful person, she discovers a whole farmful of people wallowing, self-thwarted, in chronic misery and simply makes them stop it. Old Adam Lambsbreath has been mournfully ‘clettering’ the dishes with a thorn twig for many decades. Flora recommends a nice little mop with a handle, and buys one for him when she next goes to town. Flora is like Lewis Carroll’s Alice, unintimidated by people who talk nonsense, refusing to be drawn into their mad world.”

“In a manner that ought surely to endear her to modern literary critics, Flora enters the novel Cold Comfort Farm and alters it from within. In psychoanalytical terms, Flora is the Superego organizing the Id. And in symbolic terms, well, don’t get me started on the symbolism. Part of the brilliance of the book is that by creating a character – Mr Mybug, the corpulent and harmless devotee of D. H. Lawrence, who sees every bud as a phallus and every hill as a breast – who actually personifies symbolism, Gibbons releases her readers from their usual symbolism alertness duties – and then playfully gets away with loads of it under their noses. For heaven’s sake, it’s Flora that lets the bull out.”

“In the Listener in 1981, Libby Purves quotes Stella’s saying of Cold Comfort Farm: ‘I think, quite without meaning to, I presented a kind of weapon to people, against melodrama and the over-emphasising of disorder and disharmony, and especially the people who rather enjoy it. I think the book could teach other people not to take them seriously, and to avoid being hurt by them.’”

“It’s the light-heartedness that is perhaps the key. But it is also the sheer comic confidence of the authorial voice that makes this book a joy.”

Quote: Judith’s breath came in long shudders. She thrust her arms deeper into her shawl. The porridge gave an ominous, leering heave; it might almost have been endowed with life, so uncannily did its movements keep pace with the human passions that throbbed above it. (Chapter III)

Quote: The trout-sperm in the muddy hollow under Nettle Flitch Weir were agitated, and well they might be. The long screams of the hunting owls tore across the night, scarlet lines on black. In the pauses, every ten minutes, they mated. It seemed chaotic, but it was more methodically arranged than you might think. (Chapter IV)

Quote: Adam laughed: a strange sound like the whickering snicker of a teazle in anger. (Chapter V)

Quote: Flora sighed. It was curious that persons who lived what the novelists call a rich emotional life always seemed to be a bit slow on the uptake. (Chapter VI)

Quote: A thin wind snivelled among the rotting stacks of Cold Comfort, spreading itself in a sheet of flowing sound across the mossed tiles. Darkness whined with the soundless urge of growth in the hedges, but that did not help any. (Chapter XVI)

“In the end, the most important aspect of Cold Comfort Farm is how modern it is. The narrative voice is direct, the plot is simple, the comedy is completely undamaged by the passage of time, and the literary playfulness is awesome. Meanwhile, its underlying serious point about people invoking childhood misery – ‘I saw something nasty in the woodshed!’ – and using it as a means to exempt them from normal life, and have power over their families, is utterly relevant to the modern world.”

“In the biography, Oliver recalls with pleasure a stage production of Cold Comfort Farm in which the biggest laugh went to the moment when the Hollywood producer, Mr Neck, is removing Seth from the farm, and runs into Aunt Ada Doom. ‘I saw something nasty in the woodshed!’ she cries. ‘Did it see you?’ he asks.”

6 responses to “Something Nasty in the Woodshed”

The first thing I thought of reading this was Dorothy Sayers commentary in “The Divine Comedy.” She notes Dante, rather than presenting the reader with allegorical types, uses people who personify (for the purposes of the story) the types. Not Lust, but Francesca da Rimini, who let “love,” sweep her into adultery.

And whose stories were well-known at the time.

I love-love-love Cold Comfort Farm. And the miniseries/movie made from it in 1995 is a treasure, and hits every single beat in the novel, as well as being adorably cast – including Rufus Sewell as the lust-and-film-crazed Seth Starkadder.

I was once asked in an interview which fictional character I most identified with, and of course it’s the very practical and organized Flora Poste.

Huh. I ordered this book after a being reminded of it at rightwingknitjob-dot-com in a post made there in late December. It arrived yesterday and I have not yet had a chance to read it. But given a second endorsement, I guess I will have to. My late wife loved the movie.

I remember she also pointed out that Flora changed too. As I recall Flora had wanted to be a writer and was putting the rest of her life on hold because she figured that was how to do it. Except Elfine was doing the same thing with her poetry.

I recall she ends the movie, at least, by heading off with the interesting gentleman with the aeroplane, with the implication being, she has decided to actually live life and just write rather than putting together any great plan to ensure her literaturary success.

It’s been a while since I saw it, so I’m probably missing parts. And that may have just been in the movie, not part of the book, so don’t know. Does fit the themes though.

Live life and just write is a better plan than putting together a great plan to ensure literary success. A lot of wannabe writer spend so much time planning to write they never get around to actually writing.

I think it was Harry Harrison who once observed there a lot more people that enjoy having written than actually writing. That is to say they enjoy the perks and acclaim they receive from having written something than they do the act of putting words on paper.