[— Karen Myers —]

As writers of fiction, the craft we practice is that of telling narratives. We’re storytellers. But storytelling isn’t necessarily all that straightforward as a concept, whether in traditional tales or ad hoc exercises around the campfire.

There’s an obvious anthropological benefit to understanding who people are by what they do, being able to predict their reactions — just like lions or wildebeests. It’s obviously a survival trait in any human group.

The point of archetypes is that we understand the “how” of them — what they are like instrumentally. We know how they will react to circumstances. What we don’t know is the “why” of them, how they feel inside. They’re a “given” element in a story.

Ballads and the Icelandic Sagas focus on this sort of archetypical character treatment, masterworks of showing, not telling.

The interiority of a character’s thoughts are very much a feature of modern literature. The ballad, the saga, the epic — they show you what a character does and what he says. They don’t dwell on what he thinks, his internal analysis of his own motives, nor do they try to explain those motives by other means. They assume that the hearer of the story understands the character by what he does.

Does anyone have difficulty understanding Achilles in the Iliad? The fatal actions of the lovers in Little Musgrave? The schemes of the Coyote in the Roadrunner cartoons? No one needs to explain these characters, since it is their words and deeds that do that for us. And if that’s not good enough (e.g., the enigmatic Roadrunner), the mystery is left deliberately unexplained, for us to wonder about.

It is difficult, however, to point to this in modern literature. The “show, don’t tell” recommendation for writing fiction is based more on increasing vividness by having characters carry the story and not relying on intrusive authorial explanation. But modern literature is full of characters who explain themselves for the benefit of the reader, who tell the reader all too much about what they are thinking and doing and why, as a way of engaging the reader’s understanding.

We didn’t use to find that necessary.

(quoting myself…)

The Hero’s Journey used to be something observed from the outside, using the assistance of archetypes. “Jack traded his family’s cow for some magic beans” introduces you to the sort of feckless idiot who does that. “Jack was fascinated by the beans” is rather different from “Jack was bored with his walk to the market and that cow was making things harder for him by trying to snatch at the grass as they went. Why couldn’t she treat him better than his family who never trusted him?”

Even Queen Elizabeth chose not to “look into men’s souls”.

Novel writers, however, do look into men’s souls, to show us their private thoughts, which even they may not understand well enough to explain their actions, if they wanted to try.

Styles change. The traditional tales have given way to an authorial presence in men’s heads, and stories feel incomplete (or old-fashioned) without at least some of that, even if it’s only for the hero, with everyone else still opaque and provided with just enough presence that they can be identified as a “type” with relatively predictable behaviors.

That’s no longer just a crafting of narrative — it’s a direct view into internal emotional engagement at a new level. And that requires its own craft.

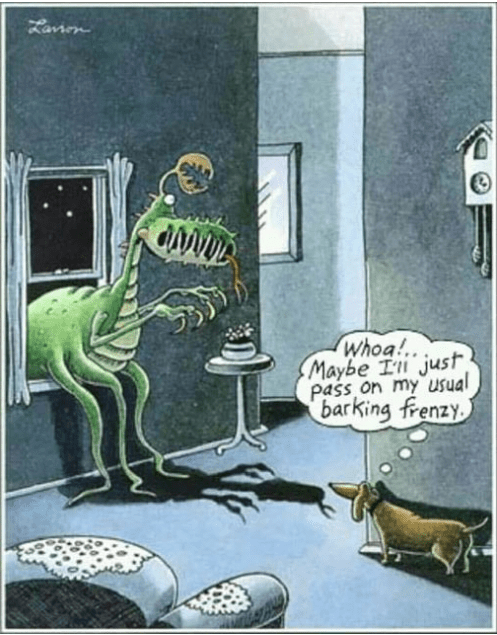

…. and thus (finally) the illustration above as an exemplar of using reflection of emotion to engage a reader.

It may be a single panel, but you are still expected to read it from left to right, so it has a sequence. First you are surprised, and then the character is surprised — and your surprise becomes broader and more amused by his. And none of that would work if you couldn’t see his thoughts, his specific internal reaction that you can so easily sympathize with.

This is using the emotion of surprise to reveal character. The reader is surprised first, and then sees the character’s surprise. And the point of the comedy is the echoing of the internal reactions, not a narrative of actual action.

It’s like a house of mirrors, in its way. And utterly modern.

This was a difficult article to write to get my point across, and I hope it succeeded. I have a background in dead languages and traditional literature, so it frequently strikes me.

Do you ever think about the choices you make about whose thoughts to reveal, and why, as a specific craft? The waves of emotional causes and consequences that flesh out a narrative, that show the thoughts so that they can reflect off the reader?

Ever notice that this isn’t an old or traditional idea (at least in the West)?

7 responses to “Reflected emotions”

Every point of view choice affects that. There are points of view I have included or excluded because of that.

I think you did a great job explaining your thoughts! It is something that I think I have subconsciously observed but did not connect the dots. I have to wonder if your point about how stories “of old” used to rely on the action of the character to tell the reader/listener about them rather than their internal story is one of the reasons why I have trouble reading certain kinds of literature…like the Bible. (There, I said it). I’ll say something else a professed Christian is not supposed to say: I get bored with reading it. It’s not because I cannot be bothered or that I am a disbeliever. It’s because my mind is searching for some way to “feel” the people in the Bible and the stories being told end up being more mysterious to me than revelatory. Maybe that’s on purpose.

Or certain parts of the Lord of the Rings (in particular whenever the Rohirrim/Theoden are involved. It’s as if there is NO internal view at all and it drives me nuts to the point where I just skip over it all entirely, although I know I shouldn’t).

I know I’m revealing myself as a kind of mundane reader and not too bright when it comes to certain things, but its probably because, as you surmise, that this “modern” way of telling/reading a story is so ingrained in me that the Old Ways feel foreign and disconnected in a lot of ways. I had less trouble reading parts of Beowulf than I did the Bible, but I had to read a watered down version of the Iliad (homeschool) in order to gain some sort of “internal” understanding.

Youve got me thinking to go back and reread the Old Works with this POV youve presented. Maybe it will “click” better with me.

Boy howdy, would I be delighted to find someone looking at the old material afresh!

If you like adventure and are tempted by the sagas, I would recommend a modern translation of Grettir (The Saga of Grettir / Grettir the Outlaw – variants of that title). It’s short, it’s vivid, and it’s an excellent example of “the early novel of hundreds of years ago”. You will be surprised at how modern it feels (except for the internal POV absence).

The Bible is, indeed, an exemplar of the “the old material”, not only relying on archetypical characters and how they behave (how else can you create a parable?), but creating new ones (the Woman at the Well).

Tolkien is immersed in what is called “The Matter of Britain” (as opposed to the Matter of France: Roland, Charlemagne. etc.) and presents not just the narrative material but much of the stylistic approach, beautifully wrapped for modern tastes. When he falls into a more detached view, he is indeed echoing his source material and its methods of presentation.

Part of what people admire in reading things like the Iliad (esp. in the original) is this flavor of archaicism in how to deal with psychology, and how individuals are distinguished from cardboard characters. When you read it in the original, the language makes it particularly revealing. Athena literally seizes Achilles by the forelock when she speaks to him. People don’t have thoughts — thoughts seize them.

For more on adventuresome sagas, as compared to the Brennu Njalsaga, the Sage of Burnt Njal, which mostly about Icelandic lawsuits (granted, Viking lawsuits tended to involve swordplay and people’s houses getting burned down…) there’s also Egil’s Saga. And the Hrolf Kraki Saga, which is set in ‘olden times’, by the standards of late medieval Icelanders anyway, and has a lot of magic along with the swordplay. As well as a werebear as one of the heroes. It was turned into a fine novel by Poul Anderson, too.

OT but I also enjoy the sense of humor you can find in those stories. Like in the one saga where some men try breaking into the house of a man called Gunnar so they can kill him. The door is barred, so one man gets lifted up to look into a window — and promptly falls back, dying, a spear wound under his heart. He is asked if Gunnar is there and says, “I don’t know. You can look for yourself. I can tell you this much, his war-spear is home,” and immediately dies.

I couldn’t get into the Anderson novel. The characters were not attractive enough without the interior view to add sympathy.

Anderson’s Norse fantasies were pretty brutal. He said in an introduction for one of them that he didn’t want people to lose sight of how civilization is not something to take for granted.

Those sorts of quips are exactly what the Icelanders remembered, when they finally wrote the stories down. These are historical family stories, you realize, not (deliberate) inventions.

When they had the vote in the Althing and decided to go for the White Christ instead of the Red Thor, the decisive argument was that Valhalla was all very well, but not everyone could hope for that, while everyone was at least eligible for heaven. Seemed like a better deal for them.

A very logical (and argumentative) demographic, with long memories and a taste for lawsuits. The Althing is the organizational inspiration for all the parliamentary governments in the Anglo-sphere.